Every single question has been covered.

Note: These are model hints. The detailed model answer with review would be posted later.

UPSC Sociology 2023 – Paper 1

1 (a). What is the distinctiveness of feminist methods of social research? Comment. 10

The feminist method of social research is distinct from traditional research methods in several key ways:

- Focus on Gender and Power: Feminist research places a central emphasis on the examination of gender as a social construct and how power dynamics related to gender shape various aspects of society. It seeks to uncover and challenge patriarchal norms and inequalities.

- Intersectionality: Feminist research recognizes that gender doesn’t exist in isolation; it intersects with other social identities such as race, class, sexuality, and more. This intersectional approach allows for a more nuanced understanding of how multiple factors influence individuals’ experiences.

- Participatory and Collaborative: Feminist research often involves collaboration with the subjects of study, viewing them not just as research subjects but as active participants. This approach promotes a more democratic and inclusive research process.

- Qualitative Methods: Feminist research frequently employs qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and ethnography to capture the lived experiences and narratives of individuals. These methods are well-suited to exploring complex social issues.

- Reflexivity: Feminist researchers are encouraged to be reflexive about their own positions, biases, and power dynamics. They critically examine their roles in the research process and how their perspectives may influence the findings.

- Advocacy and Social Change: Feminist research often aims not only to understand social issues but also to bring about positive change. Researchers may engage in advocacy, activism, or policy recommendations based on their findings.

- Ethical Considerations: Feminist research pays close attention to ethical considerations, particularly in relation to issues of consent, confidentiality, and the potential for harm. It seeks to ensure that research respects the dignity and autonomy of participants.

- Narrative and Personal Stories: Feminist research values personal narratives and stories as legitimate forms of data. These stories can provide important insights into the experiences of individuals, especially in contexts where dominant discourses may silence certain voices.

- Critique of Traditional Research: Feminist researchers often critique and challenge the assumptions and biases of traditional research methods, highlighting their limitations in addressing issues related to gender and power.

Ann Oakley argues that there is a feminist way of conducting interviews that is superior to a more dominant, masculine model of such research. She suggests making the research more collaborative and in developing a relatively intimate and nonhierarchical relationship with the interviewees. While interviewing new mothers, she allowed the participants to ask questions and even gave them help and advice, if asked for.

Criticism:

- Ray Pawson argues that such epistemologies run into problems when those being studied continue to see the world in terms that the researcher finds unconvincing. Example: Feminist researchers are unlikely to be dominant. Also, it puts all the emphasis on studying the experiences of the oppressed, without studying the oppressors (in this case, men). Studying oppressors might reveal at least as much about the nature of oppression as studying the oppressed.

- He is also critical of the plurality of different viewpoints, as sometimes such viewpoints may contradict one another. This may lead to the path of relativism. They are no longer trying to explain the society as it really is, but are reduced to accepting all viewpoints as equally valid.

However, Benton and Craib state that feminist standpoint epistemology adopts a consistent position and offers a socio-historical account of the gendered process of knowledge creation. Feminism has developed concepts like mothering, sexual division of labour and gender socialization, which provide a base for making sense of other cultures. It also has a point when it argues that values should be involved in the production of social science knowledge

Feminist theory has been instrumental in driving societal changes that have improved women’s rights and equality, with the work of theorists such as Simone de Beauvoir, Judith Butler, and bell hooks being particularly influential.

1 (b). Discuss the relationship between sociology and political science. 10

- Overlapping Interests: Sociology and political science share some overlapping interests and subject matter. Both disciplines explore social institutions, power structures, group dynamics, and the impact of societal factors on individuals and communities.

- Study of Power and Authority: Both fields examine power and authority in society, but they approach these topics from different angles. Political science often focuses on the formal structures of government, political systems, and the behavior of governments and politicians. Sociology, on the other hand, looks at power dynamics in a broader societal context, including how power is distributed, exercised, and resisted in various social settings.

- Scope of Analysis: Political science typically concentrates on the formal, public, and governmental aspects of power and politics, including topics like elections, policy-making, international relations, and governance. Sociology has a broader scope, encompassing not only politics but also family, education, religion, economics, and other social institutions, examining how they influence and are influenced by political processes.

- Methods and Approaches: The two disciplines often use different research methods and approaches. Political science commonly employs quantitative methods and surveys to analyze political behavior, while sociology often uses qualitative methods, ethnography, and participant observation to explore social phenomena in-depth.

- Levels of Analysis: Political science frequently operates at the level of the state, government, and international relations, while sociology often examines smaller social units such as communities, groups, and individuals. However, there is an area of overlap when studying how political decisions and policies impact various social groups.

- Interdisciplinary Bridges: Despite their differences, sociology and political science can intersect in areas such as political sociology, which examines the relationship between political and social processes, or in the study of social movements and their political implications.

- Policy and Advocacy: Both disciplines can contribute to policy analysis and advocacy. Political scientists often engage in policy research, while sociologists study the social impacts of policies. They may collaborate in providing evidence-based recommendations for addressing societal issues.

In summary, sociology and political science are related fields within the social sciences that study different aspects of human society and behavior. While they have distinct focuses and methodologies, there are areas of overlap and opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration, particularly in analyzing the complex interplay between social structures and political processes.

||🎯 Our Courses ||

1 (c). How does the dramaturgical perspective enable our understanding of everyday life? 10

The dramaturgical perspective, developed by sociologist Erving Goffman, is a framework that likens everyday life to a theatrical performance. It suggests that individuals engage in impression management, presenting themselves to others in ways they want to be perceived.

This perspective enables a deeper understanding of everyday life in several ways:

- Front Stage vs. Back Stage: Goffman’s concept of front stage (where performances occur) and back stage (where individuals can be themselves) helps us recognize the different roles people play in various social contexts. Understanding this duality allows us to interpret behavior and interactions more comprehensively.

- Impression Management: People strategically manage their impressions to influence how others perceive them. Recognizing this helps us understand why individuals may act differently in different situations and how they use verbal and non-verbal cues to shape perceptions.

- Face-to-Face Interactions: The dramaturgical perspective sheds light on the intricacies of face-to-face interactions. It explains how individuals engage in “facework” to maintain their own and others’ positive social identities, navigate conflicts, and manage emotions in social situations.

- Role Performance: By viewing everyday life as a series of roles individuals play, we can analyze how societal expectations, norms, and scripts influence behavior. People enact roles such as parent, student, employee, or friend, and understanding these roles helps us make sense of their actions.

- Social Hierarchies: Goffman’s perspective helps us recognize the role of power, status, and social hierarchies in interactions. Those in positions of authority may have more control over the “stage,” while others may have limited influence in shaping the performance.

- Stigmatization: The dramaturgical perspective can help us understand the experiences of individuals facing stigmatization. Goffman’s work on “stigma management” explores how individuals cope with being socially devalued or marginalized, which is relevant in understanding the challenges faced by various groups.

- Group Dynamics: It provides insights into group dynamics, including how individuals cooperate and coordinate their performances within social groups. It also helps us understand how group norms and roles influence individual behavior within the group.

- Social Media and Online Identities: In the digital age, the dramaturgical perspective is relevant to understanding how people curate and manage their online personas, emphasizing the performance aspect of social media interactions.

In essence, the dramaturgical perspective offers a framework for analyzing and interpreting the complex, dynamic nature of human interactions in everyday life. It encourages us to see social interactions as performances, revealing the strategies people use to navigate social situations, maintain social order, and present themselves in a way that aligns with their self-concept and societal expectations. This perspective enhances our understanding of social behavior, communication, and identity in the intricacies of daily life.

1 (d). Is reference group theory a universally applicable model? Elucidate. 10

Universal applicable model:

- First world – Samuel Stouffer – American soldier study

- Indian context- MN Srinivas Sanskritization

- In Tribal societies – anticipatory socialization of tribes like Nagas to the demands of modernity

- Institutional sphere – referent power in politics ( French & Raven ) , resocialization of trainees in bureaucracy, role modeling

Whether reference group theory is universally applicable depends on several factors:

- Cultural Variability: Cultural norms and values play a significant role in shaping reference groups and their influence on individuals. What is considered a relevant reference group can vary greatly between cultures. Thus, the theory may not apply universally across all cultural contexts.

- Individual Differences: People have unique psychological and social characteristics that affect how they perceive and use reference groups. Some individuals may be more susceptible to the influence of reference groups than others, depending on their personality, values, and life experiences.

- Contextual Factors: The relevance and impact of reference groups can change depending on the specific context and the nature of the decisions or behaviors being considered. For example, reference groups may be more influential in consumption choices than in career decisions.

- Evolving Social Dynamics: Social structures and dynamics are not static; they evolve over time. What constitutes a reference group and its significance can change as societies develop and undergo social, economic, and technological transformations.

- Individual Goals and Motivations: People may have varying goals and motivations, which can influence whether they choose to conform to or differentiate from their reference groups. Some individuals may actively seek to distance themselves from their reference groups.

1 (e). Do you think that the boundary line between ethnicity and race is blurred? Justify your answer. 10

Basic Differences between race and ethnicity

- Biological vs cultural

- Inherited vs chosen

Examples of racial categories include White, Black, Asian, Native American, etc.Examples of ethnic groups include Hispanic, Latino, Chinese, Irish, African, etc.

The boundary line between ethnicity and race is often blurred, and this blurring arises from the complex and intertwined nature of these concepts. Here’s a justification for this assertion:

- Social Construct: Both ethnicity and race are social constructs rather than biological realities. They are created by society to categorize and differentiate people based on certain characteristics. Because these constructs are socially defined, they can be fluid and subject to interpretation, leading to overlap.

- Interconnected Identities: Individuals often identify with multiple ethnic and racial groups simultaneously. For example, someone might identify as both African American (racial identity) and Nigerian American (ethnic identity). This intersectionality blurs the line between ethnicity and race.

- Cultural and Ancestral Heritage: Ethnicity often encompasses elements such as shared culture, language, customs, and ancestral heritage. These factors are sometimes closely associated with racial categories, leading to the fusion of ethnic and racial identities.

- Historical and Geographic Variation: The way ethnicity and race are defined can vary significantly across different societies and historical periods. What constitutes a racial or ethnic group in one context might not be the same in another, contributing to the blurring of boundaries.

- Social Perception: How individuals are perceived and categorized by others can blur the lines between ethnicity and race. People may be racially categorized based on physical traits, while their ethnicity is linked to cultural or national characteristics.

- Political and Social Context: Political and social factors, such as government policies, affirmative action programs, and social movements, can influence how people identify themselves and how they are categorized by others. These dynamics can further complicate the distinction between ethnicity and race.

- Intersectionality: Intersectional identities, which involve multiple dimensions of identity including race and ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and more, highlight how these categories can overlap and intersect in individuals’ lived experiences.

- Self-Identification: Ultimately, how individuals choose to identify themselves is a significant factor. Some people may prioritize their racial identity, while others may emphasize their ethnic or cultural identity, and still, others may blend aspects of both.

- Ethnic fluidity in globalization

2 (a). What, according to Robert Michels, is the iron law of oligarchy? Do lions and foxes in Vilfredo Pareto’s theory, essentially differ from each other? Substantiate. 20

Key components of Michels’ theory:

- Leadership Concentration: Michels argued that in organizations, leaders naturally emerge to handle administrative tasks, decision-making, and coordination. These leaders, often due to their expertise and efficiency, gradually consolidate power and influence within the organization.

- Oligarchical Inevitability: As leaders gain more authority and responsibility, they tend to form an oligarchy, a small ruling group. This oligarchy, Michels contended, eventually becomes detached from the broader membership’s interests and can act in its own self-interest rather than in the best interest of the organization as a whole.

- Bureaucracy: Michels saw bureaucracy as a key mechanism through which the iron law of oligarchy operates. As organizations grow in size and complexity, they require administrative structures and hierarchies. These structures often lead to leaders becoming increasingly insulated from rank-and-file members.

- Democracy’s Paradox: Michels noted a paradox within democratic organizations. While such organizations are founded on the principles of equality and participation, they tend to develop oligarchical tendencies over time. He argued that this phenomenon occurs because effective decision-making often necessitates specialization and delegation of authority.

- Potential Mitigation: Michels did not propose an absolute, irreversible state of oligarchy but rather an ongoing tension between democratic ideals and oligarchical tendencies. He suggested that democracy could be preserved through measures such as frequent rotation of leaders, transparency, accountability mechanisms, and active participation of the membership.

In essence, the “iron law of oligarchy” highlights the inherent tension between democratic ideals of participation and equality and the practical realities of organization and leadership. Michels’ work has been influential in the study of political parties, labor unions, and various other large organizations, as it underscores the challenges of maintaining truly democratic practices within them.

In Vilfredo Pareto’s sociological and political theory, he introduced the concept of “lions” and “foxes” as metaphors to describe two distinct types of elites or rulers within a society. These terms are used to differentiate between the characteristics and behavior of these elites. Here’s a substantiation of the essential differences between lions and foxes in Pareto’s theory:

Lions:

Characteristics: Lions are depicted as strong, traditional, and conservative rulers. They often represent the old aristocracy or established elites in a society.

Stability: Lions tend to promote social stability and order, but they can also be seen as oppressive and resistant to societal progress.

Behavior: Lions are seen as leaders who rely on force, authority, and the status quo to maintain their power. They are typically resistant to change and innovation.

Foxes:

Characteristics: Foxes, in contrast, are characterized by their cunning, adaptability, and willingness to change. They are often associated with emerging or revolutionary elites.

Behavior: Foxes are more flexible and pragmatic in their approach to power. They are open to new ideas and willing to use various strategies to achieve and maintain their dominance.

Instability: While foxes can bring about change and innovation, they can also be seen as contributing to social instability and uncertainty.

Substantiating the Differences:

Historical Context: Pareto’s theory was developed during a time of significant social and political change in Europe, including the decline of traditional aristocracies and the rise of new elites. In this context, the contrast between lions and foxes reflects the changing dynamics of power.

Power Strategies: The key distinction lies in their approaches to power. Lions rely on traditional authority and established norms, while foxes are more adaptable and employ various strategies to gain and maintain power. This reflects how different elites may use distinct methods to achieve their objectives.

Impact on Society: Lions tend to uphold existing social structures and hierarchies, emphasizing stability but potentially stifling progress. Foxes, on the other hand, can bring about change, challenge the status quo, and introduce innovation, often leading to social upheaval.

Longevity of Power: Lions may have a longer-lasting grip on power due to their control of established institutions and resources, while foxes may experience shorter periods of dominance but with the potential for more significant transformations during their rule.

It’s important to note that in Pareto’s theory, these terms are not necessarily judgments of value; rather, they are descriptive of different types of elites and their characteristics. Furthermore, the distinction between lions and foxes highlights the complex and evolving nature of elite rule in societies undergoing periods of transition and change.

2 (b). What is historical materialism? Examine its relevance in understanding contemporary societies. 20

Historical materialism is a foundational concept within Marxist theory developed by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. It provides a framework for understanding the development of human societies, their economic structures, and their historical evolution. Historical materialism is based on the idea that material conditions and economic factors are central in shaping the course of history.

Here are its key features:

Primacy of Material Conditions: Historical materialism asserts that the material conditions of a society, including its means of production (tools, technology, resources), mode of production (how goods and services are produced and distributed), and the economic relationships between classes, are the driving forces behind historical change.

Class Struggle: It emphasizes the significance of class struggle in shaping history. Historical materialism posits that societies are divided into classes with conflicting interests, primarily the bourgeoisie (owners of the means of production) and the proletariat (working class). This class struggle is a central engine of historical change.

Dialectical Materialism: Historical materialism is influenced by dialectical materialism, a philosophical framework that examines the development of ideas and social systems through the interplay of contradictions and conflicts. It views history as a process of contradictions and resolution.

Historical Development: Historical materialism sees human history as a series of distinct stages or modes of production, each characterized by specific economic structures and class relations. These stages include primitive communism, slave society, feudalism, capitalism, and socialism/communism. The transition between these stages is driven by class struggle and changes in the mode of production.

Social Superstructure: Historical materialism distinguishes between the economic base and the superstructure of society. The economic base includes the means and relations of production, while the superstructure encompasses institutions, culture, politics, ideology, and religion. The superstructure is influenced by and serves to maintain the economic base.

Revolutionary Change: Historical materialism predicts that the inherent contradictions and conflicts within capitalism will lead to its eventual downfall and the emergence of a classless society (communism). This transition is expected to occur through a proletarian revolution, where the working class seizes control of the means of production.

Materialist Interpretation of Ideology: Historical materialism argues that ideology, including religious, political, and cultural beliefs, is shaped by and serves the interests of the ruling class. It is seen as a reflection of the dominant economic structure and class relations.

Empirical Analysis: Marxists use historical materialism to analyze concrete historical developments, social movements, and economic systems. It offers a lens through which to understand how societies evolve and how class dynamics influence political, economic, and social changes.

Critique of Capitalism: Historical materialism provides a powerful critique of capitalism by examining its inherent contradictions, such as exploitation and inequality, and by predicting its eventual demise as a historical stage.

Historical materialism remains relevant in understanding contemporary societies as it provides a lens through which to analyze the underlying economic structures, class dynamics, and historical development of these societies.

Here are some specific examples of its relevance:

Understanding Economic Inequality:

Example: Examining contemporary societies, we can use historical materialism to understand the persistence and exacerbation of economic inequality. It allows us to analyze how the capitalist mode of production contributes to the concentration of wealth and power in the hands of a few (the bourgeoisie), while the majority (the proletariat) faces economic insecurity.

Globalization and Imperialism:

Example: Historical materialism helps in understanding the dynamics of globalization and imperialism. It can shed light on how powerful capitalist nations dominate and exploit less-developed countries through economic, political, and cultural means, perpetuating global inequalities.

Labor Movements and Workers’ Rights:

Example: In contemporary labor movements and struggles for workers’ rights, historical materialism can help analyze the class struggle between labor (proletariat) and capital (bourgeoisie). It provides a framework for understanding the conflicts over wages, working conditions, and the distribution of profits.

Technological Change and Capitalism:

Example: Historical materialism can be used to analyze the impact of technological advancements on contemporary societies. It helps us understand how automation and digitalization can lead to changes in the mode of production, affecting employment, class relations, and social structures.

Crisis Theory:

Example: During economic crises such as the 2008 financial crisis or the COVID-19 pandemic, historical materialism provides a perspective to examine the root causes within the capitalist system. It highlights how such crises are often linked to the contradictions and instability inherent in capitalism.

Ecological proletarianization:

Example: In the context of environmental challenges like climate change, historical materialism can be applied to analyze how the pursuit of profit and economic growth within a capitalist framework often leads to the overexploitation of natural resources and environmental degradation.

Social Movements and Activism:

Example: When examining contemporary social movements, historical materialism can help us understand the motivations and objectives of various groups. It allows for an analysis of how different social classes and economic interests intersect within these movements.

Rise of Populism and Political Shifts:

Example: In the rise of populist movements and political shifts in various countries, historical materialism can be used to explore the underlying economic grievances and class dynamics that contribute to these political changes.

Global Capital Flows:

Example: Historical materialism can illuminate how the mobility of capital in the global economy affects workers and communities. It helps in understanding the power dynamics between transnational corporations and national governments.

Criticism of Historical Materialism

Overemphasis on Economic Factors:

Example: In the case of nationalist movements, historical materialism may not fully account for the role of cultural identity and ideology in driving political mobilization. For instance, the Catalan independence movement in Spain is shaped by both economic grievances and cultural identity, which go beyond economic determinism.

Simplified Class Analysis:

Example: In post-industrial societies, the lines between the traditional bourgeoisie and proletariat can blur, making it challenging to fit individuals neatly into these categories. New forms of employment, such as gig work or creative industries, may not align with the classic Marxist class distinctions.

Teleological Assumptions:

Example: The collapse of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc challenged the teleological aspect of historical materialism, as it was not a transition toward communism but rather a different historical outcome.

Neglect of Non-Class Identities:

Critique: Critics argue that historical materialism can overlook the significance of non-class identities, such as gender, race, and ethnicity, in shaping historical events and social structures.

Example: Feminist critiques point out that historical materialism does not adequately address gender-based oppression and the ways in which patriarchy interacts with capitalism. The women’s liberation movement and its goals are not fully explained within the traditional framework of historical materialism.

Eurocentrism and Eurocentric Bias:

Critique: Some scholars argue that historical materialism, as developed by Marx and Engels, has a Eurocentric bias and may not adequately address non-European or non-Western historical processes.

Example: Critics contend that historical materialism may not provide a comprehensive understanding of anti-colonial struggles, decolonization, and the dynamics of post-colonial societies, as it was primarily developed in a European context.

Lack of Attention to Subjectivity:

Critique: Critics suggest that historical materialism can sometimes neglect individual and collective subjectivity—the thoughts, beliefs, and motivations of people—as influential factors in historical change.

Example: When analyzing political revolutions, such as the Arab Spring, a sole focus on economic conditions may not capture the role of popular aspirations for democracy and freedom, which are driven by subjective desires for political change.

It’s important to note that while these criticisms highlight limitations and challenges, historical materialism continues to be a valuable framework for analyzing many aspects of societal development. Scholars have also sought to address some of these critiques through adaptations and extensions of the theory. Additionally, historical materialism remains a subject of ongoing debate and revision within the fields of sociology, political science, and history.

2 (c). What are variables? How do they facilitate research? 10

In sociological research, variables are key elements that researchers study, measure, and analyze to understand relationships, patterns, and phenomena within society. Variables are characteristics or attributes that can vary or change, and they play a crucial role in facilitating research by allowing researchers to systematically investigate and draw conclusions about social phenomena.

Here’s how variables work and their significance, illustrated with specific examples:

Independent Variables: These are variables that researchers manipulate or examine to see if they have an effect on other variables. They are often the causes or factors that are believed to influence change in the research.

Example: In a study examining the impact of education on income levels, “education level” is the independent variable. Researchers manipulate or categorize participants based on their education levels (e.g., high school diploma, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree) to see how it affects their income.

Dependent Variables: These are the outcomes or effects that researchers measure and analyze to see if they are influenced by the independent variables. Dependent variables are the results or changes that researchers are interested in explaining.

Example: In the same study, “income level” is the dependent variable. Researchers measure participants’ income to see if it varies based on their education level, which is the independent variable.

Control Variables: Control variables are other factors that researchers want to keep constant or account for in their study to ensure that the relationship between the independent and dependent variables is not distorted by external factors.

Example: If researchers are studying the impact of education on income, they may control for factors like age, gender, and years of work experience to isolate the effect of education.

Categorical Variables: These variables represent categories or groups and are often used to describe characteristics of individuals or groups in the study. They are typically nominal or ordinal in nature.

Example: In a study on political affiliation, “Democrat,” “Republican,” and “Independent” are categorical variables used to classify participants based on their political beliefs.

Continuous Variables: Continuous variables are numeric variables that can take on a range of values and can be measured with great precision. They are often used in quantitative research.

Example: Age is a continuous variable, as it can take on any value within a certain range (e.g., 25.5 years, 32.8 years). Researchers can use age as a continuous variable to explore its relationship with other variables, such as income or voting behavior.

Qualitative Variables: These variables represent non-numeric data and are often used in qualitative research. They can capture attributes, characteristics, or textual data.

Example: In a qualitative study exploring perceptions of social justice, “participant narratives” are qualitative variables. Researchers collect and analyze participants’ stories, experiences, and opinions to understand their perspectives on social justice issues.

Variables facilitate research by allowing for systematic investigation, analysis, and the testing of hypotheses. They provide a structured way to measure and quantify social phenomena, which enhances the rigor and replicability of sociological studies. By carefully defining and examining variables, researchers can uncover patterns, relationships, and insights that contribute to our understanding of complex social issues.

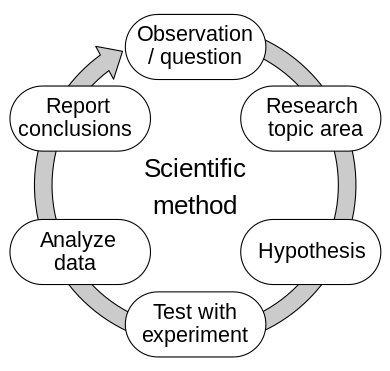

3 (a). What are the characteristics of scientific method? Do you think that scientific method in conducting sociological research is foolproof? Elaborate. 20

The scientific method is a systematic and logical approach to discovering how things in the universe work. It is the technique used in the construction and testing of a scientific hypothesis. It’s a method of research where a problem is identified, data is gathered, a hypothesis is formulated from this data, and the hypothesis is empirically tested.

The scientific method, as defined by Goldhaber and Nieto (2010), is a collection of techniques employed to explore phenomena, acquire new knowledge, or revise and integrate existing knowledge. The phrase “scientific method” gained widespread acceptance in the 20th century, with John Dewey’s 1910 book, How We Think, popularizing its use. In their book Research Methodology, Goode and Hatt perceive science not as a separate field but as a methodological approach to examining reality based on sensory experiences.

Steps involved in the scientific method

Several renowned sociologists and thinkers, including Theodorson and Theodorson, Kenneth D. Bailey, Horton and Hunt, have outlined systematic steps involved in the scientific method of investigation.

Utility/significance of scientific method:

Reliability: The scientific method ensures reliability by making use of direct observations and proven theories. It involves empirical collection of data and application of unique scientific methods for each case, which provide strong evidence to support successful theories. For instance, in a study analyzing optimal weight patterns in relation to age, the researcher would collect data, formulate hypotheses, and then apply appropriate formulas and theories to either accept or reject those hypotheses.

Objectivity: Objectivity is fulfilled in scientific research as all facts are validated through direct observations. This approach produces unbiased conclusions as the collected data is not skewed towards any preconceived notions. It is the primary responsibility of the researcher to deliver efficient and objective inferences.

Falsifiability: One of the key aspects of the scientific method is the capability of getting falsified. This involves deriving conclusions or inferences by applying hypothesis testing on collected data. The testable nature of these hypotheses lends credibility to the research findings and supports the conclusion of the research.

Control: Scientific methods enable control over the results of the research. Conclusions are derived from testing hypotheses against various variables. If any crucial variable changes, the conclusion can be calibrated accordingly. Various experiments are conducted, and the final result is based on the study of each variable involved. This facilitates the establishment of cause-effect relationships and the research conclusion isn’t affected by the impact of any random variable.

Consistency: The scientific method ensures the consistency of conclusions. When the research process is repeated, there is a high likelihood of finding consistent results. This validation of findings underscores the reliability of results obtained through the scientific approach.

Critiques of the Scientific method:

The scientific method, while a foundational element in modern research, has been examined critically by several scholars across various fields, including sociology, history, and philosophy of science. Notable figures like Michael Polanyi, Ludvik Fleck, Karl Popper, Imre Lakatos, Thomas Kuhn, and Paul Feyerabend have exposed the sociocultural underpinnings of the scientific method. They’ve analyzed the practice of science in real-life scenarios, showing how ideals of pure science such as universality, objectivity, and value neutrality often turn out to be more ideological than factual when put into practice.

Key criticisms of the scientific method include:

Heuristic Model: Thomas Kuhn (1962) questioned the gap between the theory and practice of science. He argued that scientists operate with preset notions and theories, subtly influencing their observations and measurements. Once a theory becomes accepted, it often becomes untestable and forms the basis for subsequent theories, establishing a norm.

Feminist Critique: Feminist scholars like Evelyn Fox Keller, Sandra Harding, Donna Haraway, and Helen Longino challenge the scientific method’s claims to knowledge, truth, rationality, and objectivity. They dispute the notion of a detached, neutral observer, contending that all knowledge is ‘situated,’ shaped by the knower’s social, cultural, and political values. They question the concept of objectivity as represented in the scientific method.

Epistemological Anarchism: Paul Feyerabend, in his book ‘Against Method,’ proposed the notion of epistemological anarchism. He contended that science doesn’t progress by adhering to universal, fixed rules, viewing such an idea as unrealistic, harmful, and restrictive to science itself. Feyerabend advocated for a democratic society where science coexists with other social institutions like religion and education, or even magic and mythology, on an equal footing.

Divinized Status: David Parkin likened the epistemological approach of science to divination, suggesting that science could be viewed as a means of gaining insight into particular questions, much like divination in a Western context.

Falsification: In ‘The Logic of Scientific Inquiry,’ Karl Popper argued for a more critical spirit in science. He proposed that scientific inquiry should focus on uniqueness rather than patterns, emphasizing falsification over verification. Popper believed in ‘verisimilitude’ or partial truths rather than the absolute truth pursued by pseudoscience.

Reality Layers: Theodor Adorno believed that reality exists in multiple layers, and the scientific method, with its emphasis on quantitative analysis, often neglects qualitative, non-observable aspects of reality.

Replication Crisis: Despite the scientific method’s insistence on reproducibility, it is often challenging to replicate results in fields like medicine, causing difficulty in disproving results.

3 (b). How do you assess the changing patterns in kinship relations in societies today? 20

Assessing changing patterns in kinship relations in contemporary societies requires a sociological lens that takes into account evolving family structures, roles, and norms. Here’s how sociologists approach this assessment, along with contemporary examples:

Demographic Changes: Sociologists analyze demographic trends such as declining birth rates, delayed marriage, and rising divorce rates. These trends influence family size and composition.

Example: In many Western societies, there’s a trend of delayed marriage and childbearing, with more individuals opting for cohabitation or remaining single. This is altering traditional family structures.

Changing Gender Roles: Sociologists examine how shifts in gender roles within families impact kinship relations. This includes changes in women’s participation in the workforce and men’s involvement in childcare and household tasks.

Example: The increasing number of dual-income households and fathers taking on caregiving roles reflect shifts in traditional gender roles.

Non-Traditional Family Forms: Sociologists study non-traditional family forms, such as same-sex couples, blended families, and single-parent households. These forms challenge conventional kinship norms.

Example: The legalization of same-sex marriage in many countries has led to an increase in same-sex couples forming families with legal recognition.

Technological Advances: Sociologists explore how technology, including social media and online communication, affects kinship relations. It can facilitate or hinder family connections.

Example: Social media platforms enable families to maintain long-distance relationships and stay connected, but they can also lead to issues like “phubbing,” where in-person interactions are disrupted by smartphone use.

Migration and Transnational Families: Migration patterns create transnational families, where members live in different countries. This has implications for kinship, as families adapt to separation and reunification.

Example: Families separated by international borders due to work or immigration often rely on digital communication to maintain relationships.

Aging Populations: Sociologists study the challenges posed by aging populations, including issues related to elder care, intergenerational relationships, and changing norms around filial piety.

Example: In Japan, a rapidly aging society, changing patterns of elder care and support have emerged as younger generations face new challenges in fulfilling traditional filial obligations.

Globalization and Cultural Diversity: Sociologists consider the impact of globalization on kinship, as diverse cultural practices and norms interact and influence family structures.

Example: The practice of arranged marriages persists in some cultures even as societies become more globalized, leading to a negotiation of traditional and modern values within families.

Legal and Policy Changes: Sociologists examine how changes in laws and policies, such as those related to marriage, divorce, and adoption, shape kinship relations.

Example: Legal recognition of same-sex marriage and adoption has expanded kinship possibilities for LGBTQ+ individuals and couples in various countries

In summary, sociologists assess changing patterns in kinship relations by examining demographic shifts, changing gender roles, non-traditional family forms, technological influences, migration, aging populations, globalization, and legal changes. Contemporary examples illustrate how these factors interact to reshape the ways in which individuals form, maintain, and experience kinship in today’s societies.

3 (c) Is Weber’s idea of bureaucracy a product of the historical experiences of Europe? Comment. 10

Max Weber’s idea of bureaucracy is indeed a product of historical experiences, and his work on the subject was heavily influenced by the historical context in which he lived. Weber, a German sociologist writing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was deeply affected by the social and political developments of his time. Here’s a commentary on how historical experiences shaped Weber’s concept of bureaucracy:

Industrialization and Modernization: Weber’s era was marked by rapid industrialization and the transformation of agrarian societies into modern industrial states. The growth of large-scale organizations, both in the private and public sectors, was a defining feature of this period. This historical context influenced Weber’s observation and analysis of bureaucratic structures.

Rise of the Modern State: The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the consolidation and expansion of modern nation-states. Governments needed efficient administrative systems to manage increasingly complex societies. Weber’s work on bureaucracy was, in part, a response to the demands of modern governance.

Weber’s Experience: Max Weber himself had direct experience with the bureaucracy of the German Empire. He worked as a university professor and often had to navigate bureaucratic institutions. His observations and frustrations with bureaucratic processes likely contributed to his interest in studying them.

Historical Contingencies: Weber’s understanding of bureaucracy was shaped by the historical contingencies of his time. He observed the rationalization of authority and the increasing importance of bureaucratic organizations in both public and private sectors. These observations informed his theory of bureaucracy as a rational-legal form of authority.

Response to Societal Changes: Weber’s work on bureaucracy was, in part, a response to the challenges posed by the changing nature of authority and organization in modern society. His historical context demanded an analytical framework to understand and address the issues arising from the rise of bureaucracies.

In Weber’s influential essay “The Theory of Social and Economic Organization” (1922), he outlined the characteristics of an ideal-typical bureaucracy, emphasizing features like hierarchy, division of labor, formal rules, impersonality, and specialized roles. His conceptualization of bureaucracy was influenced by the historical processes and challenges of his time, but it also aimed to provide a theoretical framework applicable to various organizational contexts. Overall, Max Weber’s idea of bureaucracy is a product of his historical experiences and observations of the changing social and administrative landscape of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work continues to be influential in understanding the functioning of bureaucratic organizations in contemporary societies.

4 (a). Do you think that common sense is the starting point of social research? What are its advantages and limitations? Explain. 20

Common sense can serve as a starting point for social research, but it comes with both advantages and limitations.

Advantages of Using Common Sense as a Starting Point in Social Research:

Familiarity: Common sense is based on everyday experiences and observations that people encounter in their daily lives. It is familiar and relatable to most individuals, making it an accessible starting point for research.

Practicality: Common sense can provide initial hypotheses or research questions without the need for extensive background knowledge or formal training in social science. It allows individuals to engage in informal, exploratory research.

Intuition: Common sense often relies on individuals’ intuition and instincts, which can lead to insightful questions or observations that merit further investigation.

Cultural Sensitivity: Common sense can incorporate cultural and contextual knowledge, as it is often shaped by the social and cultural environment in which individuals live. This can be valuable in understanding specific social phenomena.

Limitations of Using Common Sense as a Starting Point in Social Research:

Subjectivity: Common sense is subjective and influenced by personal biases, beliefs, and cultural norms. It may not always align with empirical evidence or reflect broader patterns in society.

Lack of Systematic Inquiry: Common sense is typically not based on systematic inquiry or research methods. It relies on anecdotal evidence and may overlook complex social processes.

Inaccuracy: Common sense can be inaccurate or oversimplified. What seems obvious or intuitive to one person may not hold true in all situations or for all individuals.

Limited Scope: Common sense tends to focus on individual experiences and immediate observations. It may not address broader social structures, historical context, or systemic issues.

Inadequate for Complex Research: When dealing with complex social phenomena or conducting in-depth research, common sense may not provide the depth of understanding or explanatory power required.

Generalization: Common sense may lead to overgeneralization, where observations or beliefs about a small sample of cases are applied universally. This can lead to stereotypes and biases.

Confirmation Bias: People tend to seek information that confirms their preexisting beliefs or common-sense notions. This confirmation bias can hinder objective research.

In summary, common sense can serve as an initial starting point for social research, especially in generating research questions or hypotheses. However, it should be viewed as a preliminary step rather than a substitute for systematic, rigorous research methods. Researchers should be aware of its limitations, subjectivity, and potential for bias, and they should complement common-sense insights with empirical data, theoretical frameworks, and rigorous research methodologies to gain a deeper and more accurate understanding of social phenomena.

4 (b). How is poverty a form of social exclusion? Illustrate in this connection the different dimensions of poverty and social exclusion. 20

Poverty is indeed a form of social exclusion because it deprives individuals and communities of access to essential resources, opportunities, and participation in various aspects of society. Social exclusion, in the context of poverty, goes beyond a lack of income; it encompasses multiple dimensions that limit individuals’ full integration into society. Here are the different dimensions of poverty and social exclusion, illustrated with specific contemporary examples:

- Economic Exclusion:

- Dimension: Lack of access to adequate income and economic resources, leading to material deprivation and exclusion from economic participation.

- Example: In many countries, there are marginalized communities or individuals who struggle to secure stable employment, earn a living wage, or access basic necessities like housing and nutritious food.

- Educational Exclusion:

- Dimension: Limited access to quality education and educational opportunities, hindering personal and social development.

- Example: Children from low-income families often face educational exclusion. They may attend underfunded schools with fewer resources and experienced teachers, limiting their educational outcomes.

- Healthcare Exclusion:

- Dimension: Inadequate access to healthcare services, including medical treatment, preventative care, and health insurance.

- Example: In many countries, individuals without health insurance may avoid seeking medical care due to cost concerns. This leads to disparities in health outcomes and perpetuates social exclusion based on health status.

- Social Exclusion:

- Dimension: Being marginalized from social networks, community involvement, and participation in cultural and recreational activities.

- Example: Homeless individuals often experience social exclusion. They may be isolated from family and friends, lack access to community resources, and face stigma that prevents them from participating in social activities.

- Political Exclusion:

- Dimension: Limited participation in political processes, decision-making, and civic engagement.

- Example: In some regions, marginalized groups, such as indigenous communities or refugees, may face political exclusion due to barriers in accessing citizenship, voting rights, or representation in government.

- Digital Exclusion:

- Dimension: Limited access to digital technologies, the internet, and digital literacy, which hinders participation in the digital economy and modern communication.

- Example: Communities in rural or economically disadvantaged areas may lack reliable internet access, limiting their ability to access online education, job opportunities, and social connections.

- Spatial Exclusion:

- Dimension: Geographical isolation or segregation, often seen in urban slums or rural communities lacking infrastructure and services.

- Example: Urban slums in many developing countries are characterized by poor housing, inadequate sanitation, and limited access to public services, leading to spatial exclusion.

- Cultural Exclusion:

- Dimension: Discrimination or marginalization based on cultural background, ethnicity, religion, or language.

- Example: Discrimination against minority ethnic groups can lead to cultural exclusion, limiting opportunities for education, employment, and social integration.

- Generational Exclusion:

- Dimension: When poverty is passed down from one generation to the next, resulting in limited opportunities for upward mobility.

- Example: Families trapped in intergenerational poverty may struggle to provide their children with the resources and opportunities needed to escape poverty, perpetuating a cycle of exclusion.

Contemporary examples of these dimensions of poverty and social exclusion can be found worldwide. Efforts to address poverty often require comprehensive approaches that tackle each dimension, recognizing that social exclusion is a multifaceted challenge that affects individuals and communities in diverse ways.

4 (c). Highlight the differences and similarities between totemism and animism. 20

Animism and totemism are both belief systems and spiritual traditions that ascribe significance to natural elements, animals, and objects, but they have distinct characteristics and cultural contexts. Here’s an examination of their similarities and differences:

Similarities:

Sacred Natural Elements: Both animism and totemism attribute spiritual or supernatural qualities to natural elements, such as animals, plants, rocks, and geographic features. These elements are often seen as having symbolic or sacred significance.

Belief in Spiritual Forces: In both belief systems, there is a belief in spiritual forces or energies that exist in the natural world. These spirits are thought to influence human life and events.

Ancestor Veneration: Animism and totemism often involve the veneration or reverence of ancestors or ancestral spirits. Ancestors are considered to be an integral part of the spiritual realm and may play a role in guiding or protecting the living.

Differences:

Totemism’s Focus on Totems: Totemism places a particular emphasis on totems, which are symbolic representations of natural elements or animals. Each clan or group typically has its totem, and members of that group often regard themselves as spiritually connected to that totem.

Clan-Based: Totemism is often organized around clans or kinship groups. Each clan associates itself with a specific totem, and this totem serves as a symbol of the clan’s identity and unity. Totemic symbols are used to represent these clans.

Role of Totemic Myths: Totemism frequently involves the transmission of myths and stories related to totems. These myths explain the origins, behaviors, and qualities of the totemic animals or natural elements. They often serve as a source of guidance and morality for the group.

Emphasis on Social Structure: Totemism often has a strong influence on the social structure and organization of the community. Clan membership, determined by one’s totem, can influence marriage, inheritance, and social roles.

Geographic Variation: Totemism can vary significantly from one culture to another, with different cultures having their own unique totems, symbols, and practices. It is more closely tied to specific cultural traditions and may not be as universal as animism.

Animism’s Broader Scope: Animism is a broader belief system that extends beyond clan-based totems. It encompasses a wide range of beliefs in spirits and spiritual forces that may not be tied to specific totemic symbols. Animism can be found in various cultural contexts worldwide and is not limited to specific clans or groups.

Spiritual Relationships: Animism often emphasizes the idea of individual relationships with spirits and natural elements. These relationships can be highly personal and may not be organized into clan-based structures.

In summary, both animism and totemism are belief systems that attribute spiritual significance to natural elements and animals. However, totemism places a specific focus on clan-based totems, with an emphasis on social organization and totemic myths, whereas animism encompasses a broader range of spiritual beliefs and is not necessarily tied to clan structures or totemic symbols. These belief systems are shaped by the cultural contexts in which they emerge.

5 (a). Examine the relevance of corporate social responsibility in a world marked by increasing environmental crises. 10

Relevance of CSR

- Wertrational Action: Rational means to achieve value-oriented goals

- Decision to switch to virtual business meetings: cuts carbon footprint form Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Exhibitions (MICE) Market

- Investment in sustainable business activities: ESG ( Economic Social Governance)

Areas in which companies can focus on:

- Energy consumption and efficiency.

- Carbon footprint, including greenhouse gas emissions.

- Waste management.

- Air and water pollution.

- Biodiversity loss.

- Deforestation.

- Natural resource depletion.

- Eco-friendly office and business travel policies

- Funding to organizations engaged in environmental and energy conservation and livelihood enhancement of the marginalized communities of the tribal, coastal, slum areas.

Challenges:

- Money laundering activities via Environmental NGOs

- Greenwashing products

5 (b). How is civil society useful in deepening the roots of democracy? 10

According to Cohen and Arato, civil society is a constitution of voluntary associations, groups, and movements that are products of the free exchange of ideas in a democratic framework and that also seek to keep a permanent check on the powers of the state in the interest of citizens’ freedom.

Civil society can play a role in checking, monitoring and restraining the exercise of power by the state and holding it accountable. This function can reduce political corruption, which is pervasive in emerging democracies. It can force the government to be more accountable, transparent, and responsive to the public, which strengthens its legitimacy.

Role of society in preventing democratic erosion –

- The first and most basic role of civil society is to limit and control the power of the state. Of course, any democracy needs a well-functioning and authoritative state. But when a country is emerging from decades of dictatorship, it also needs to find ways to check, monitor, and restrain the power of political leaders and state officials. Civil society actors should watch how state officials use their powers. They should raise public concern about any abuse of power.

- Checking corruption: Another function of civil society is to expose the corrupt conduct of public officials and lobby for good governance reforms. Even where anti-corruption laws and bodies exist, they cannot function effectively without the active support and participation of civil society. They should lobby for access to information, including freedom of information laws, and rules and institutions to control corruption.

- Promote political participation: NGOs can do this by educating people about their rights and obligations as democratic citizens and encouraging them to listen to election campaigns and vote in elections. NGOs can also help develop citizens’ skills to work with one another to solve common problems, debate public issues, and express their views.

- Civil society organisations can help to develop the other values of democratic life: tolerance, moderation, compromise, and respect for opposing points of view. Without this deeper culture of accommodation, democracy cannot be stable. These values cannot simply be taught; they must also be experienced through practice. We have outstanding examples from other countries of NGOs—especially women’s groups—that have cultivated these values in young people and adults through various programs that practice participation and debate.

- Civil society also can help to develop programs for democratic civic education. Civil society must be involved as a constructive partner and advocate for democracy and human rights training.

- Civil society is an arena for the expression of diverse interests, and one role for civil society organisations is to lobby for the needs and concerns of their members, as women, students, farmers, environmentalists, trade unionists, lawyers, doctors, and so on. NGOs and interest groups can present their views to parliament and provincial councils, by contacting individual members and testifying before parliamentary committees. They can also establish a dialogue with relevant government ministries and agencies to lobby for their interests and concerns.

- Another way in which civil society can strengthen democracy is to provide new forms of interest and solidarity that cut across old forms of tribal, linguistic, religious, and other identity ties. Democracy cannot be stable if people only associate with others of the same religion or identity. When people of different religions and ethnic identities come together on the basis of their common interests as women, artists, doctors, students, workers, farmers, lawyers, human rights activists, environmentalists, and so on, civic life becomes richer, more complex, and more tolerant.

- Civil society can provide a training ground for future political leaders. NGOs and other groups can help to identify and train new types of leaders who have dealt with important public issues and can be recruited to run for political office at all levels and to serve in provincial and national cabinets.

- Civil society can help to inform the public about important public issues. This is not only the role of the mass media, but of NGOs which can provide forums for debating public policies and disseminating information about issues before parliament that affect the interests of different groups, or of society at large.

- They can play an important role in mediating and helping to resolve conflict. In other countries, NGOs have developed formal programs and training of trainers to relieve political and ethnic conflict and teach groups to solve their disputes through bargaining and accommodation.

- Civil society organisations have a vital role to play in monitoring the conduct of elections. This requires a broad coalition of organisations, unconnected to political parties or candidates, that deploys neutral monitors at all the different polling stations to ensure that the voting and vote counting is entirely free, fair, peaceful, and transparent. It is very hard to have credible and fair elections in a new democracy unless civil society groups play this role.

Because civil society is independent of the state doesn’t mean that it must always criticize and oppose the state. In fact, by making the state at all levels more accountable, responsive, inclusive, effective—and hence more legitimate—a vigorous civil society strengthens citizens’ respect for the state and promotes their positive engagement with it. A democratic state cannot be stable unless it is effective and legitimate, with the respect and support of its citizens. Civil society is a check, a monitor, but also a vital partner in the quest for this kind of positive relationship between the democratic state and its citizens.

5 (c). What functions does religion perform in a pluralistic society? 10

- Social cohesion and solidarity among different communities over festivals. Example: Festivals like Diwali, Christmas and Ramzan fosters brotherhood and mutual cooperation among members of all faiths.

- Scope for interfaith dialogue to resolve differences, focusing on the common values of all religions.

- Spirit of accommodation and tolerance: Peaceful society, economic development in the region via festivals, trade and commerce

- Education function: Schools attached to churches and temples

- Emergence of personalized religion, sects and cults: giving meaning and purpose to life,

promoting physical and psychological well-being, motivating people to work for positive social change.

5 (d). Analyze critically David Morgan’s views on family practices. 10

David Morgan is a renowned sociologist who has made significant contributions to the field of family studies. His work focuses on the social construction of family practices and the ways in which they are shaped by various social, cultural, and historical factors.

One of the strengths of Morgan’s work is his emphasis on the contextual nature of family practices. He recognizes that family dynamics and practices are not universal but are shaped by cultural and historical specificities. This perspective allows for a nuanced understanding of how families function in different societies and challenges essentialist notions of family structures.

Morgan’s research also highlights the importance of power dynamics within families. He examines how gender, class, and other social hierarchies influence family practices and shape the division of labor, decision-making processes, and access to resources within households. By shedding light on these power dynamics, Morgan’s work contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the complexities of family life.

In his first book, Social Theory and the Family (1975) he suggested that, in order to understand what happens within families, we must understand gender hierarchy. He examined the once broadly held idea that the roles of men and women were just “naturally” different, alongside the feminist argument that family life was based on the unpaid domestic labour of women, which gave men more power both inside and outside the family, and that this was oppressive to women.

From here, he went on to develop the highly influential concept of “family practices”, those relationships and activities that are constructed – perceived by family members and shaped by historical and social processes – as being to do with family matters, wherever these occur, both inside and outside the domestic setting. In Family Connections (1996) and, elaborating on his ideas, in Rethinking Family Practices (2011), David proposed a radical and profound change, shifting the focus from the noun “the family” to the verb “doing family”, and towards the many different possibilities in relation to what and who can constitute a family.

Criticisms:

However, one potential criticism of Morgan’s views is that they may overlook the agency and individual experiences of family members. While he acknowledges the influence of social structures, there is a risk of downplaying the role of personal choices and subjective interpretations of family practices. A more balanced approach would involve integrating both structural and agency perspectives to provide a holistic understanding of family dynamics.

Furthermore, some critics argue that Morgan’s work could benefit from a more intersectional lens. While he addresses the influence of social hierarchies on family practices, there is room for deeper exploration of how factors such as race, ethnicity, and sexuality intersect with gender and class to shape family experiences. By incorporating an intersectional perspective, Morgan’s analysis could provide a more nuanced understanding of the diverse ways in which families are shaped by multiple axes of power.

In conclusion, David Morgan’s work on family practices offers valuable insights into the social construction of families and the influence of social, cultural, and historical factors on family dynamics. While his emphasis on contextual dynamics and power structures is commendable, a more balanced approach that incorporates agency and intersectionality could enhance his analysis.

5 (e). Does women’s education help to eradicate patriarchal discriminations? Reflect with illustrations. 10

- Challenge stereotypes like, women being weaker in comparison to men, women being incapable of reaching heights in their career domain. Example: female CEOs like Ginni Rometty of IBM, Indra Nooyi of PepsiCo,etc.

Contribute to economic development and scientific milestones: Examples: development of Crispr Cas9, Space Missions in India

- Challenge state patriarchy: Women in leadership positions: Panchayati Raj Institutions to Lok Sabha. Female leadership at the policy making level percolates to grassroots-level changes in behavioral and cultural practices.

- Educated mothers would educate the entire family against patriarchal discriminatory practices like son-meta preference, female foeticide etc

- Self reliance and self esteem: Improves their overall life-chances and lifestyle, confidence to pursue their ambitions and not be let down by societal and patriarchal pressures.

- Empowers decision making on female centric issues like menstruation, abortions, reproductive care

Challenges:

- Cultural lag: Educational attainments need not always translate into healthy practices. For example: Dowry system among educated families, female foeticide perpetuated by female doctors themselves for monetary benefits etc

- Proxy system in panchayats: Female leaders as proxy to their husbands

- Internalisation of patriarchal notions out of lack of alternatives (taking career breaks for taking care of family and meet obligations), being victims of patriarchal violence at home and outside (Murder of IT professional in Chennai by male friend)

- Dual shift phenomenon: Instrumental role of women increases along with, and not at the expense of reduction in care-giving role.

Female education should also be supplemented by gender sensitisation drives in society so that approach towards females changes for the better. (Schemes like Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao, 33% reservation in Lok Sabha as acknowledgement of their abilities etc are steps in the right direction).

6 (a). What are the different dimensions of qualitative method? Do you think that qualitative method helps to gain a deeper sociological insight? Give reasons for your answer. 20

Qualitative research is a type of social science research that collects and works with non-numerical data and that seeks to interpret meaning from these data that help understand social life through the study of targeted populations or places.

- typically focused on the micro-level of social interaction that composes everyday life, whereas quantitative research typically focuses on macro-level trends and phenomena.

Methods:

- observation and immersion

- interviews

- open-ended surveys

- focus groups

- content analysis of visual and textual materials

- oral history

- Participant observation

Significance

- It allows the researchers to investigate the meanings people attribute to their behavior, actions, and interactions with others.

- While quantitative research is useful for identifying relationships between variables, like, for example, the connection between poverty and racial hate, it is qualitative research that can illuminate why this connection exists by going directly to the source—the people themselves.

- s designed to reveal the meaning that informs the action or outcomes that are typically measured by quantitative research. So qualitative researchers investigate meanings, interpretations, symbols, and the processes and relations of social life.

- Produces descriptive data that the researcher must then interpret using rigorous and systematic methods of transcribing, coding, and analysis of trends and themes.

- Focus is on everyday life and people’s experiences and hence qualitative research helps in creating new theories using the inductive method, which can then be tested with further research.

- Creates an in-depth understanding of the attitudes, behaviors, interactions, events, and social processes that comprise everyday life. In doing so, it helps social scientists understand how everyday life is influenced by society-wide things like social structure, social order, and all kinds of social forces.

- This set of methods also has the benefit of being flexible and easily adaptable to changes in the research environment and can be conducted with minimal cost in many cases.

Limitations:

- scope is fairly limited so its findings are not always widely able to be generalized.

- Researchers need to ensure that they do not influence the data in ways that significantly change it and that they do not bring undue personal bias to their interpretation of the findings.

6(b). Explain Max Weber’s theory of social stratification. How does Weber’s idea of class differ from that of Marx? 20

Social stratification has been viewed differently by different scholars, the two most important ones being Karl Marx and Max Weber. The Marxian perspective provides a radical alternative to the functionalist view of the nature of social stratification. They regard stratification as divisive rather than integrative structure.

From the Marxian perspective systems of stratification are derived from the relationships of social groups to the forces of production. Marx used the term class to refer to the main Strata in all stratification systems. From the Marxian view, a class is a social group whose members share the same relationship with the forces of production. Another important work on stratification is done by Max Weber.

COMPARISON BETWEEN THE TWO:

- Like Marx, Weber sees class in economic terms. He argues that classes develop in market economics in which individuals compete for economics again. Weeber defines a class as a group of individuals who share a similar position in the market economy and by virtue of that fact receive similar economic rewards. Thus in Weber’s terminology a person’s class situation is basically his market situation. Those who share a similar class situation also share similar life chances.

- Like Marx, Weber argues that the major class division is between those who own the forces of production and those who do not.Thus those who have a substantial property holding will receive the highest economic rewards and enjoy superior life chances.

CONTRAST BETWEEN THE TWO:

- Factors other than the ownership or non-ownership of property are significant in the formation of classes. In particular, the market value of the skills of the propertyless varies and the resulting differences in economic return are sufficient to produce different social classes.

- Weber sees no evidence to support the idea of the polarisation of classes. Although he sees some decline in the number of the petty- bourgeoisie, the small property owners, due to competition from large companies, he argues that the entire white-collar or skilled manual trades rather than being depressed into the ranks of unskilled manual workers. Weber says that the white-collar middle-class expands rather than contracts as capitalism develops. He says that capitalist enterprises and the modern nation-state require a rational bureaucratic administration that involves a large number of administrators and clerical staff.

- Weber rejected the view held by some Marxists of the inevitability of the proletarian revolution.He sees no reason why those sharing a similar class situation should unnecessarily develop a common identity, recognize shared interests and take collective actions for those interests. For example, Weber suggests that the individual manual worker who is dissatisfied with his class situation may respond in a variety of ways. He may grumble at work, sabotage industry machinery and take strike action, etc. to overthrow capitalism.

- Finally, Weber rejected the Marxian view that political power is necessarily derived from economic power. He argues that class forms only one possible basis for power and that the distribution of power in society is not necessarily limited to the distribution of class inequalities.

In contemporary times both thinkers stand relevant. While the rising middle class shows signs of embourgeoisement as predicted by Weber. On the other hand, rising inequalities have further increased the class divide. There are also signs of pauperization as said by Marx. Thus both theories help us in understanding the phenomena of stratification in society.

6 (c). What are the ethical issues that a researcher faces in making use of participant observation as a method of collecting data? Explain. 20

(a) Subjectivity: coloured by personal prejudices and bias

(b) Inadequate observation: human eros in observation, or in interpretations of practices. Certain micro-phenomenon ( thoughts and attitudes) cannot be directly observed. The observer can observe only those events which take place in front of him. But that is not enough and only a part of the phenomena as a vast range of information required for the research. He can know many things about the group when he participates in the group and interacts with the group members. ( Andre Beteille’s study of caste on Sreepuram village of Tanjore was obstructed by restrictions on visiting the settlement of the Adi-dravidars)

(c) Unnatural and formal information: The members of a group become suspicious of a person who observes them objectively. In front of an outsider or stranger they feel conscious and provide only some formal information in an unnatural way. It creates bias and what the observer collects is not actual or normal thing but only formal information.